‘Elegy’, Op. 47 No. 7, the final piece in the fourth book of Lyric Pieces, published around 1888, presents challenges that are more musical than purely technical. This piece is a prime example of Grieg’s ability to convey deep feeling within a concise form. Grieg establishes the melancholic and brooding atmosphere from the outset, and it is maintained throughout. Cast in a minor key, this piece embodies the ‘light and dark’ nature of Grieg’s harmonic language, revealing a darker aspect to something seemingly innocent or innocuous. The sadness conveyed in ‘Elegy’ is subtle and introspective, rather than overtly dramatic, which requires a sensitive interpretative approach.

‘Elegy’ is in a strophic form, in which three unaltered statements of the A section (bars 1-16, 39-55, and 78-94) alternate with two unaltered statements of the B section (bars 17-38, 56-77); a three-bar codetta draws the piece to its conclusion. It is primarily in the traditionally funereal key of B minor, and both sections sustain this sombre mood.

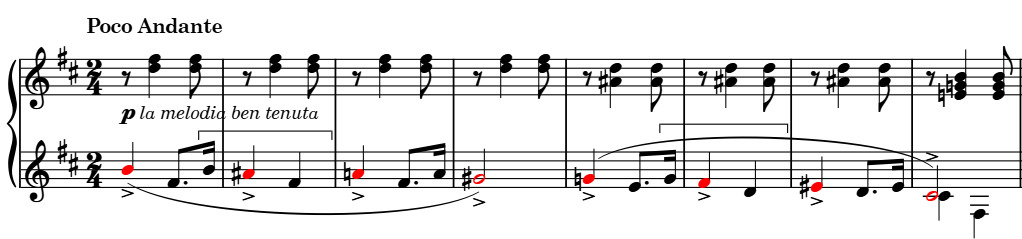

The A section introduces the main thematic material, characterized by a poignant melody, featuring the so-called ‘Grieg motif’ (think opening of the Piano Concerto, bracketed in ex. 1), which outlines a descending chromatic line (marked in red in ex. 1), B-A♯-A𝄮-G♯. Note how the outline of the second phrase, G𝄮-F-♯-E♯-C♯, also features the ‘Grieg motif’ in its final three notes. This lyrical line is central to the work’s expressive character, requiring a cantabile touch to allow it to sing. The syncopated accompaniment, which fills out the triadic harmony, remains above the melody both at the outset and when the first phrase-pair is repeated, in octaves, an octave lower. Bars 5-8 see a shift (enharmonically reinterpreting the leading-note, A♯=B𝄬) to the submediant minor. Although bar 8 sees the B𝄬/A♯ resolve to B(𝄮), the tonic note, this pitch forms part of a piquant dominant-11th chord, creating a sort-of imperfect cadence at the end of the phrase. When this phrase-pair is repeated, this cadence is not altered—as would often be the case—to conclude the paragraph with a perfect cadence. The tonal resolution and sense of closure that a perfect cadence would bring, is thereby denied.

The B section, marked by a slightly swifter tempo, intensifies the emotional landscape. The melody now moves to the right hand, while the left hand, playing just below it, adds a ‘sighing’ counterpoint composed of three descending semitones to the triadic filling. The rhythmic pattern from the A section is developed here, particularly in the third bar (bar 19) where it is intensified; the melodic idea here is also related to the ‘Grieg motif’, the descending semitone is now answered by a rising perfect fourth. The first four-bar phrase is repeated in a melodic sequence a whole-tone higher (bars 21-24), and a third repeat begins, another whole-tone up, but is extended, building to a significant climax at bar 31. moving to C♯7, then through C+6 to F♯7.

It is at this point that the movement reaches the height of its despair: an anguished A𝄮 cry, dissonant with the dominant-7th harmony initiates a four-bar bridge passage to usher in the reprise of the A-section. Note, again, the ‘Grieg motif’ in three sequential iterations, each descending chromatically. This is as close to a perfect cadence as Grieg gives us until the very end! Like so many of the Lyric Pieces, ‘Elegy’ can indeed be seen as a study in closure-avoidance.

The A and B sections are repeated before one final statement of the A section, again left hovering on the dominant-11th, is brought to a close with an additional descending fifth in the left hand—which takes us to the lowest pitch used in the work—and finally comes to rest on the tonic chord. Fading softly, ‘Elegy’ leaves us with a lasting impression of introspective lament.

Performance Suggestions

To convey the emotional atmosphere of this movement, meticulous attention to phrasing, dynamics, and articulation is essential. To bring ‘Elegy’ to life, we need an holistic approach that integrates technique with musical understanding. In other words, every technical decision should directly serve the expressive and aesthetic aims of your performance.

Grieg’s music exemplifies Nordic simplicity and economy, so offers us a valuable lesson in expressive subtlety. Aim for sincere, understated delivery rather than exaggerated drama. The emotional impact of the piece comes from its inherent beauty and directness. Note Grieg’s use of the term ‘poco’, both modifying the main tempo, and in the B section. Poco Andante and poco mosso are, in fact, virtually synonymous, meaning ‘going a little’ and ‘a little moved’ respectively, so there is hardly any increase in the B section. As I often say, less is more!

While modern English definitions most usually associate the word ‘elegy’ with a poetic lament for the dead, the original Greek term (ἐλεγείᾱ) is less specific, and can refer to any poem or song of a sad, serious, or memorialising nature on a wide range of subjects from love to war, as well as grief and loss. I find it interesting that the strophic nature of Grieg’s piece, with the unvaried repetition of clearly delineated paragraphs, gives it a songlike aspect—the passage at bars 35-38 taking an almost recitative-like quality. Ensure, then, that the melodic line is projected clearly above the accompaniment, and always has a warm, cantabile tone.

Likewise with rubato, a natural flexibility will help shape musical ideas and delineate sections, but mustn’t feel arbitrary. Your playing should never become rhythmically vague. It will help you achieve all of these things to sing through the melody, paying attention to natural inflections and places to breathe.

The accent signs here are more about giving each note, particularly within the melodic line, its appropriate weight and connection, bringing out the shape of the A-section melody, rather than indicating a strong attack. Build the crescendo in the B section carefully: the mood calls for a controlled increase of intensity rather than a sudden, harsh outburst. Both returns to the A section should feel poignant, perhaps resigned. That said, note just how much of the harmony is this piece is dissonant. Lean in to these clashes, don’t apologise for them. Perhaps more could be made of this in the reprises, to give a directional thread to the strophic structure.

This piece poses particular challenge in terms of the sustaining pedal, and Grieg’s own markings are unhelpfully sparse. Obviously, the pedal is crucial for creating the right sound-world, supporting the accompanying chords, and facilitating the left-hand legato octaves. However, imprecise pedalling can lead to a muddy sound. Experiment with half-pedal, and with varying the speed of pedal-releases, to ensure harmonies are sustained only as long as necessary, allowing the melody to sing cleanly, but avoiding an overly-dry sound. You might also consider deploying the left pedal to introduce a different tone-colour. Practise each passage with and without the pedals in order to judge how best to use it effectively. Remember, imagine the sound you want to create first, then aim to match it in your practice!

‘Elegy’ is a testament to Grieg’s genius for crafting miniature masterpieces that resonate deeply out of very little material. While not demanding extreme virtuosity, its melancholic beauty and distinctive harmonic language offer immense musical rewards.