It is almost a dirty word, a label for a kind of polite, facile music, written for the bourgeoisie, lacking the heft of more serious, ‘canonical’ works. This is ‘salon music’, and to mention it in the same breath as a Beethoven sonata or a Mahler symphony is, for some, a mark of musical illiteracy. For decades, musicologists and critics have dismissed salon music as ‘elegant’ and ‘graceful’ but never profound. It is a genre burdened with the accusation of sentimentality and superficiality—a failed, commercially-driven imitation of serious art. Yet, this dismissal does a disservice to a rich and complex genre that not only encompasses exquisite works of art but which also played a critical role in the democratisation of music. By re-evaluating salon music with a more generous ear, we will discover a world of beauty, social innovation, and emotional depth that deserves our serious attention.

I posit that this enduring, profound misrepresentation, a modern term for ‘light’, easy-listening music, is not coincidental, but a symptom of cultural re-evaluation. Salon music’s negative reputation has been so thoroughly cemented that it has in fact shaped our modern understanding of the term itself. The first step in a proper defense of this music is to untangle these two definitions, separating the historical genre from its contemporary, commercial progeny. My aim here is to dismantle this caricature, re-contextualizing the music within the intricate social, intellectual, and cultural ecosystem of the 19th-century salon. By examining the music’s function, rather than judging it in isolation, I hope to show that it was a sophisticated, multi-faceted art form. It was a catalyst for social progress, a vital professional network for serious composers, and an integral part of an holistic aesthetic experience.

Today the mention of ‘salon music’ conjures a faint, slightly condescending image: a tinkling piano in a stuffy, over-decorated drawing-room, its sentimental melodies serving as a polite background to the idle chatter of high society. The term itself has become a pejorative, a shorthand for music that is charming but ultimately frivolous, technically facile, and emotionally shallow. Loaded as it is with preconceptions of elitism and artistic superficiality, this caricature is a profound historical distortion, a faded wallpaper that obscures one of the most dynamic and essential musical ecosystems of the 19th century.

This common perception is not a recent phenomenon. It is a deeply entrenched cultural bias, established by a string of critical agendas and perpetuated for over 150 years. I argue that salon music, far from being the artistically inferior cousin to the grand works of the concert hall, was in fact an indispensable engine of 19th-century musical life. The salon was a space for radical intimacy and startling innovation, a crucial economic framework for artists, the primary vehicle for the dissemination of musical ideas before the age of recordings, and a unique sphere of agency for women who were systematically excluded from public musical power structures. To defend salon music is not merely to argue for the merit of a few forgotten miniatures; it is to reclaim a vital chapter of music history. By exploring the salon’s true socio-cultural context, confronting the historical criticisms leveled against it, analysing the music’s inherent artistic merit, and highlighting the central role of its female protagonists, we can begin to see this world not as a footnote, but as a headline.

Social Revolution in a Private Space

Before the rise of large, purpose-built concert halls around 1850, the majority of music was experienced in private homes, churches, and other intimate settings. It was in this environment that the salon concert flourished, a format so integral to the musical world that it was entirely familiar to canonical composers such as Schubert, Schumann, Chopin, and Liszt. These gatherings were more than just venues for performance; they were a hub for intellectual and artistic exchange, where members of the cultural elite would convene to discuss literature, poetry, philosophy, and political ideas in a convivial and stimulating atmosphere. The music performed was often light, lyrical, and designed to be enjoyed in a conversational context. The salon operated as a vital transactional space, bridging the gap between intimate social circles and the broader public sphere.

The 19th-century musical salon did not emerge from a vacuum. It was the direct inheritor of the intellectual and political gatherings of the Enlightenment, which provided a model for bringing together artists, thinkers, and patrons for conversation and cultural exchange. In its 19th-century incarnation, the salon became a place where the boundaries between artistic performance, social networking, and intellectual discourse blurred. These events, hosted in the spacious drawing rooms of the aristocracy and the rising upper-bourgeoisie, were exclusive affairs where guests could demonstrate their wealth, education, and cultural awareness.

The salon’s ascendancy was inextricably linked to the social and economic upheavals of the era. The Industrial Revolution created a newly affluent middle class with disposable income and leisure time, fostering a widespread demand for music education and domestic entertainment. At the heart of this domestic musical life was the piano. Technological advancements made mass-produced pianos more affordable, transforming them into a central fixture of the bourgeois home—a status symbol and an essential tool for the musical education of children, particularly daughters. This in turn created a vast new market for accessible, appealing, and playable sheet music. While its epicenter was in European capitals like Paris, Vienna, and Berlin, the salon was a global phenomenon, with vibrant, distinct musical cultures flourishing in the Americas and other parts of the world.

At the heart of this cultural ecosystem were the salonnières, the extraordinary women who curated and hosted these gatherings from their homes. These women wielded significant influence, promoting the reputations of composers from Bach to Stravinsky and shaping the musical tastes of 19th-century Europe. Contrary to an historical narrative that has sometimes focused on patriarchal dominance, these women were not oppressed figures; rather, they used their social positions—and, more often than not, considerable and independent wealth—to exercise artistic agency. Fanny Mendelssohn, for example, hosted a private concert series where she performed her own compositions. Influential salonnières included Winnaretta Singer, the Princesse de Polignac, who used her Paris salon to support composers such as Gabriel Fauré, and commissioned new works; Countess Maria Wilhelmine von Thun, who was instrumental in Mozart’s early success in Vienna; and Sara Levy, who created a salon in Berlin that welcomed people of all religious and social backgrounds and played a major role in the revival of J.S. Bach’s music. Similarly, Clara Schumann, a musical prodigy and celebrated pianist, championed the music of Brahms and Chopin in her own salon. The rise of prominent female composers, performers, and hostesses in the salon environment also caused some critics, who gendered salon music as a ‘feminine’ art form, to diminish its worth.

The Salon as Cultural Eco-System

More than just a venue, the salon was a complex and self-sustaining ecosystem. It functioned as a new system for the distribution of patronage, fundamentally altering how musicians earned a living and built their careers. Composers like Frédéric Chopin and John Field relied on the connections made in salons to secure wealthy pupils, who became their primary source of income. The status of the musician was transformed; figures like Franz Liszt and Niccolò Paganini were no longer seen as servants to the court but as celebrated, almost mythical, artistic figures whose fame was cultivated in both the concert hall and the salon.

For both established and emerging composers, the salon provided a platform to reach a sympathetic and intellectual audience, quite different from that of the concert hall, and offered not only a platform for their work but also tremendous social, moral, and financial support. It was an essential part of the professional life of artists like Gabriel Fauré, who attended salons regularly and found them to be a major force in the dissemination of his music throughout his career. Furthermore, these private venues could serve as a more flexible and politically open environment than public halls, allowing audiences to engage with musical arrangements of operas that contained revolutionary themes and politically inflammatory subject matter that wouldn’t have been tolerated in other more public venues. The flourishing of the amateur musician in the 19th century created a robust market for accessible sheet music, allowing a wider public to participate directly in the musical culture of their time, and the salon was often a place where professional and sophisticated amateur musicians interacted.

This intimate setting also served as a crucial laboratory for musical innovation. Before a new work was presented in a high-stakes public concert, it was often tested and refined in the salon before a discerning audience of connoisseurs. Here, composer-pianists could perform their own works with an improvisatory freedom and nuance that was impossible in a large hall, allowing the music to evolve in performance. The salon, therefore, was not a passive repository of established traditions but an active driver of musical change. It democratised patronage beyond the old aristocracy and created the specific market conditions and aesthetic demands that allowed the quintessential Romantic piano genres—the Nocturne, the Ballade, the Impromptu—to flourish. It was, in essence, the economic and social engine that powered musical Romanticism at the personal, individual level.

The conventional narrative of the 19th century frames the rise of public concerts as the primary means of music’s democratisation. However, the evidence reveals a different, more nuanced form of democratisation occurring simultaneously within the salon movement. While public halls opened music to a broader class of people, the salon opened music to greater agency for women and provided a space for individuals from diverse social backgrounds to connect through shared artistic experiences. The intimacy of the salon, often cited as a reason for its perceived triviality, was in fact its greatest strength. It created a powerful and flexible alternative to the public sphere, a space where music was not merely performed, but actively and intentionally integrated into the very fabric of social, intellectual, and cultural life.

Accusations of Insignificance

As I explore in greater depth elsewhere, the criticisms leveled against salon music in the 19th century were specific and damning. The genre was widely considered to be elegant, polite, and graceful, but lacking any real depth or substance. Critics from the period described the music as consisting of a simple and natural melody, set to the most elementary harmony, often contrasting it with more musically sophisticated writers. Detractors have argued that it prioritises emotional expression over intellectual rigour, favoring sentimental tunes and accessible harmonies.

Beyond its perceived compositional simplicity, salon music was also accused of being commercially driven, with critics claiming its ‘sole aim is to sell, and to delude the purchaser into the idea that in playing it he is performing something worth while’. This critique emerged around the time that composers such as Liszt, Louis Moreau Gottschalk, and Henri Herz began to earn significant income from their widely published works. They were derided for their perceived habit of borrowing from the masters and using derivative techniques to impress a less-educated audience. The rise of the amateur musician and the demand for easy sheet music also led to a conflation of all salon music with the repetitive, middling-quality ‘parlour tunes’ played by amateurs.

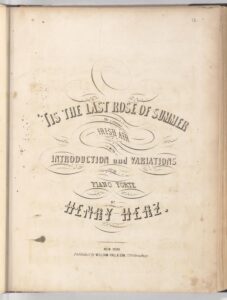

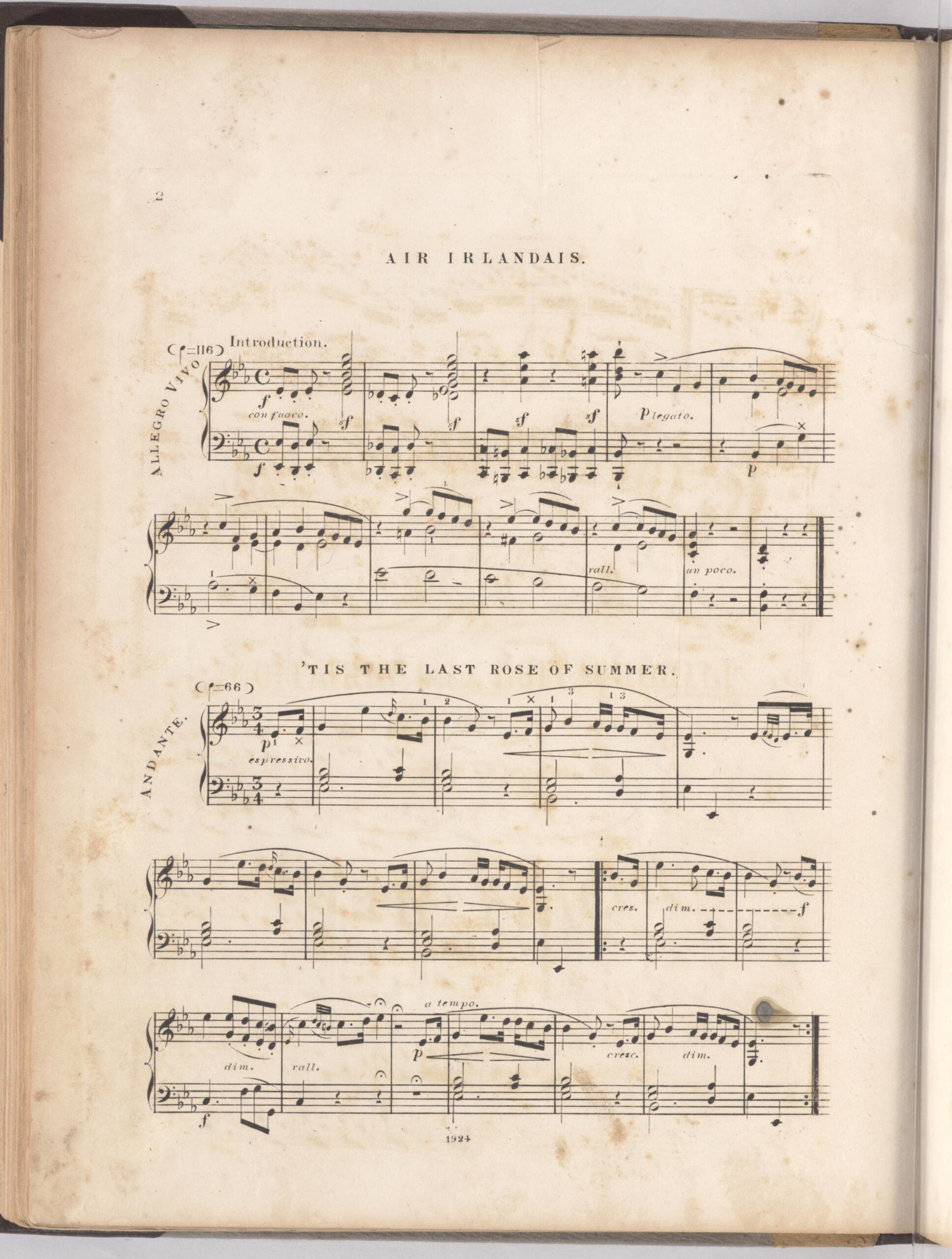

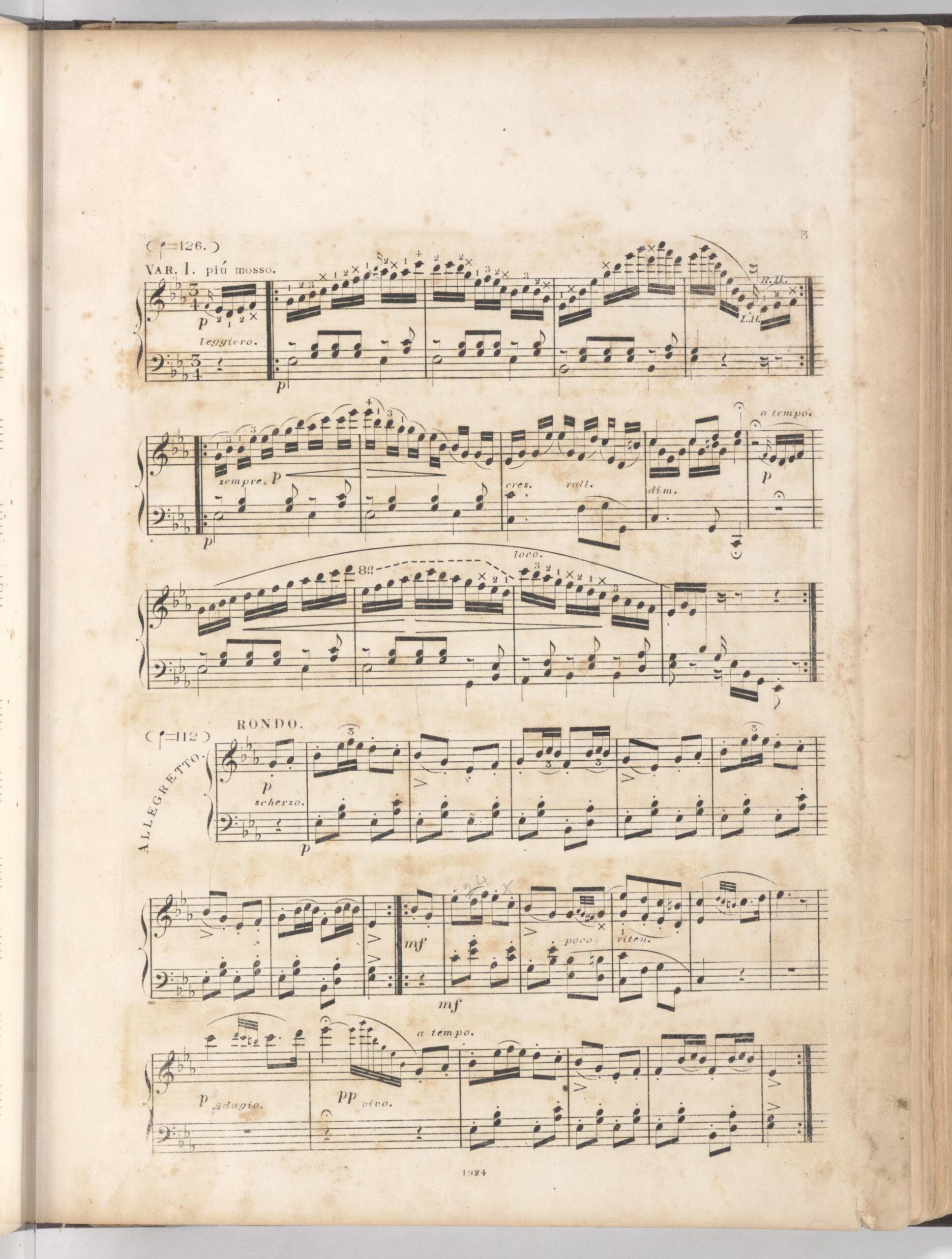

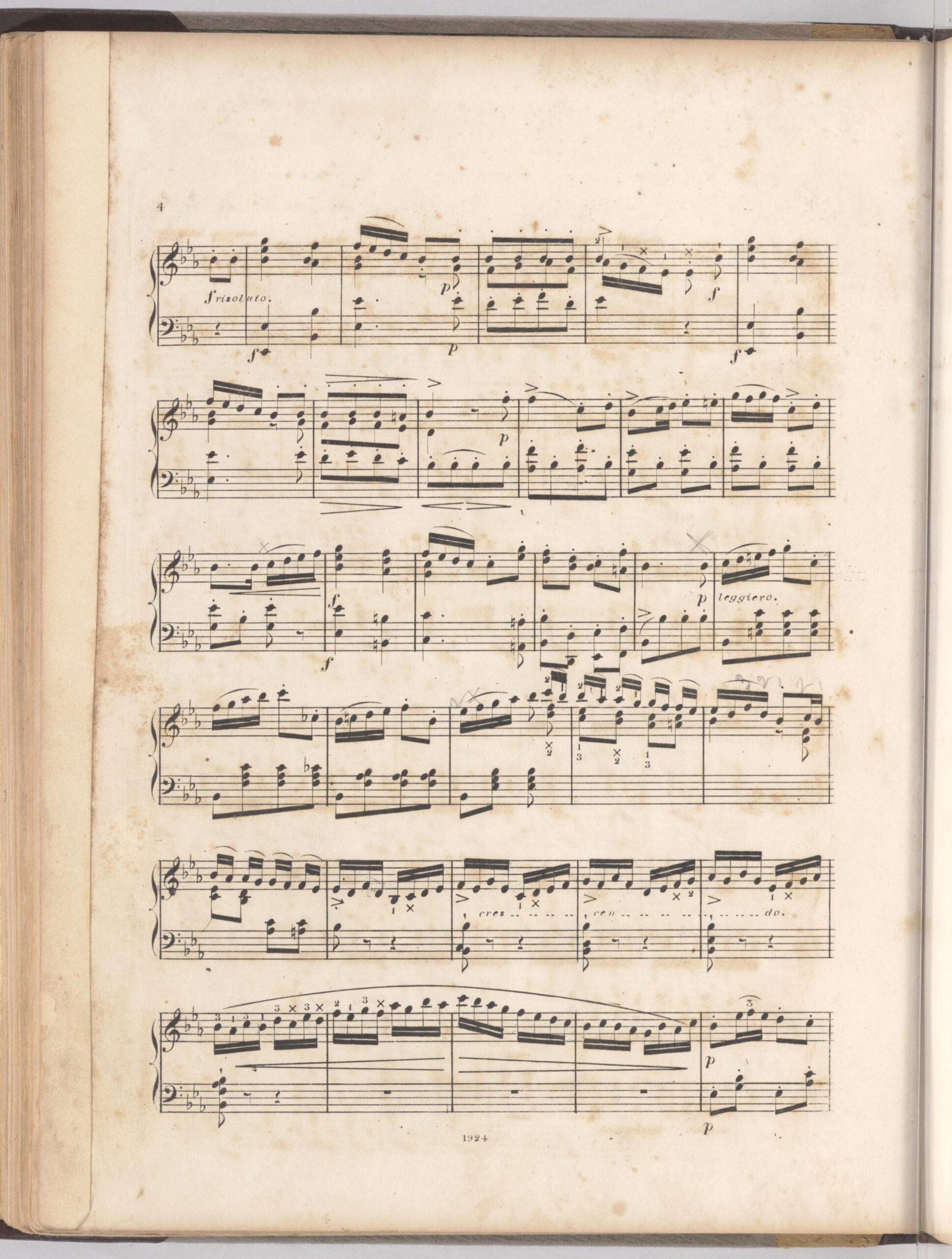

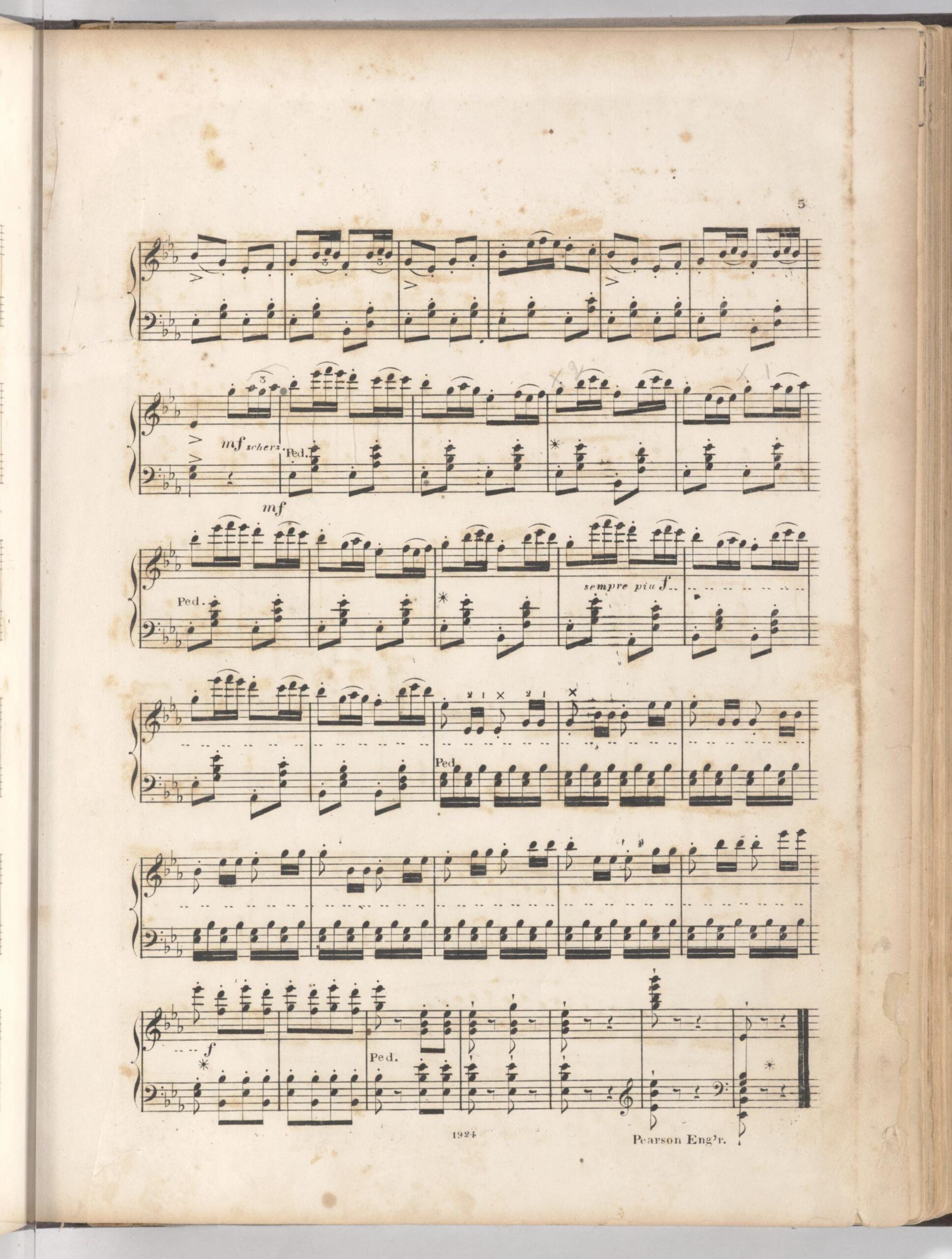

A particularly pointed criticism was that while salon music often made only slight demands on the performer’s musical insight, its technical demands could be rather more considerable. This created a paradox: music that was technically challenging to play yet intellectually shallow to interpret. For example, the variations by Henri Herz on ‘The Last Rose of Summer’ (which you can inspect below) require developed scale and arpeggio techniques and feature a long passage of rapid repeated notes, but were thought to lack poetic depth. Many pieces were seen as featuring dazzling displays of pianistic technique—rapid passages, arpeggios, and trills—that could be perceived as superficial ‘virtuosity for its own sake’. For critics and scholars, this was the central flaw—a genre that substituted a sparkling virtuosity and superficial flamboyance for genuine artistic merit. This is why Chopin—who preferred to play for small crowds and gave only around 30 public concerts in his life—was subject to a concerted critical effort to dissociate him from the genre. Scholars have argued that his ‘genius’ was not ‘limited’ by the salon, suggesting that his association with it was merely a circumstantial quirk, rather than a defining feature of his artistic output.

Critics have long characterized salon music as focusing on the overly sentimental emotional expression which lacks profundity. Robert Schumann, in 1841, famously dismissed much of it as ‘too sentimental and intellectually dull’. This critique, however, misinterprets the genre’s core aesthetic purpose. What was dismissed as mere ‘sentiment’ can be more accurately understood as the German Romantic concept of Innigkeit—a deep, authentic inwardness or intimacy. The salon was the perfect environment for this aesthetic, which valued direct emotional communication and what historian Peter Gay called ‘a vast exercise in shared solitude’. The goal was not the epic, architectural grandeur of a symphony, but the focused psychological depth of a lyric poem. Chopin’s Nocturnes, for instance, are supreme expressions of Innigkeit, designed for close listening and introspection, not for public spectacle.

The Feminine Pejorative

The charge of sentimentality is closely tied to the historical stigmatisation of the salon as an ‘effeminate’ space. This pejorative is a direct consequence of the central role women played as salonnières (hostesses and curators), patrons, and the primary demographic of amateur performers. In a male-dominated critical landscape, the salon’s association with female cultural power made it an easy target. The very qualities celebrated within the salon—grace, emotional vulnerability, elegance, intimacy—were coded as ‘feminine’, and therefore deemed less significant than the ‘masculine’ virtues of monumentality and structural rigour associated primarily with the Germanic symphonic tradition. The critical reaction to Cécile Chaminade’s music provides a stark example: her charming salon pieces were dismissed for their perceived femininity, while her more forceful concert works were criticised for being fraudulently ‘masculine’ and ‘too virile’. This reveals that the critique was not an objective musical assessment but a reflection of 19th-century gender biases. Reclaiming salon music requires re-evaluating these so-called feminine traits not as weaknesses, but as defining aesthetic strengths.

These criticisms were not just about the music itself; they were a manifestation of a fundamental ideological conflict that was reshaping 19th-century aesthetics. The rise of the public concert hall and the veneration of the ‘musical genius’, exemplified by the colossal influence of composers like Beethoven, established a new and dominant metric for musical value: profundity, complexity, and moral uplift. The salon, with its focus on elegance, sentimentality, and convivial social interaction, simply did not fit into this new paradigm. The accusations of ‘pretension’ and ‘commercialism’ stemmed directly from this cultural shift, which led to a re-evaluation of the value of art, based on its perceived seriousness and edifying public purpose. Thus a direct ideological clash with the salon’s more intimate and communal nature was created, and this clash is a key reason for the genre’s subsequent decline in reputation.

A Multi-Layered Defence – Reclaiming the Salon’s Legacy

The defence of salon music requires a fundamental re-evaluation of its purpose and context. The music was not a lesser form of ‘high art’, but a sophisticated expression of a different set of aesthetic and social values. The music’s elegance was not a sign of its superficiality, but a deliberate aesthetic choice tailored to the intimacy of the salon environment. Chopin’s career provides a powerful refutation of the critique of triviality. A master of the piano, Chopin preferred to perform for small gatherings, finding the intimate setting ideal for his exquisite piano miniatures. His Nocturnes, Preludes, Impromptus, Mazurkas, and Waltzes were considered perfect repertoire for the Salon, demonstrating that the genre was not the domain of lesser artists, but a preferred platform for a composer whose genius was defined by nuance, subtlety, and emotional depth.

Similarly, Liszt’s operatic transcriptions and works like the Grand Galop Chromatique fused dazzling technical prowess with familiar, popular melodies, showcasing a mastery of form that was both deeply expressive and highly entertaining. Norwegian composer Christian Sinding’s Frühlingsrauschen (The Rustle of Spring), is another example, with its rippling arpeggio figuration and chromatic shifts that generate dramatic restlessness. American composer Louis Moreau Gottschalk further demonstrates the innovative spirit of the genre, fusing European virtuosity with African American and Creole folk melodies in works such as Bamboula and La Savane. Chaminade’s immense contribution to the genre, with her tuneful and accessible piano pieces such as the Scarf Dance, became tremendous favourites with the public across the world.

A more profound defence of the genre necessitates a holistic view of the salon as a curated, multi-sensory experience. Recent scholarship has argued that musical and architectural design in the 18th-century Parisian salon were guided by the same aesthetic principles. The primary architectural feature of these spaces was the enfilade, a sequence of rooms with doors aligned along a single axis. Guests were led through this series of curated spaces, each one designed progressively to enrich the experience, much like a multi-movement composition. The musical form of theme and variations, a prevalent salon genre, mirrored this architectural principle of sequential elaboration. The composer would present a simple theme and then, through a series of increasingly ornate variations, build toward a brilliant finale, an experience that paralleled the progression from a subdued anteroom to a lavish grand salon. The architects of these salons were designing spaces holistically, considering how the floorplan, decorations, scents, and sounds would all complement one another. The music, the architecture, and the decor, were all structural exercises in uniformity, proportion, and progression, designed to reflect the unique identity of the salon host.

By connecting salon music to these architectural and philosophical concepts, it is possible to redefine its purpose fundamentally. The music was not an isolated object to be judged on its profundity alone, but a single, integrated component of a broader experience. The perceived ‘simplicity’ of its themes was intentional, designed to serve as a starting point for complex elaboration, to complement other elements of the salon, from conversations to decorations and scents. Furthermore, the music of the salon was inextricably linked to philosophical concepts of time and memory.

For writers and thinkers like Marcel Proust and Henri Bergson, who frequented these gatherings, the act of listening to music in a salon was a means of transporting listeners to a place of reflection, timelessness, and detachment, a space where past and present could intermingle. In his seminal work, In Search of Lost Time, Proust uses music as a literary device to spark interior reflection and a non-linear journey through memory. This is a powerful counterpoint to the criticism of salon music’s lack of profundity. The music of the salon was a central part of an intellectual and creative milieu that explored the deepest questions of consciousness, time, and memory.

The Anatomy of a Misunderstood Form: A Musical Defence

A closer look at the music itself reveals a world of compositional craft, harmonic ingenuity, and technical difficulty that belies the caricature of simplistic amateurism. The genre’s elegance often conceals its complexity, an artistic sleight of hand where supreme skill is deployed to create an effect of effortless grace. Chopin’s phrase ‘one final effort to hide all trace of effort’ springs to mind.

The Character Piece: Psychological Depth in Miniature

Brevity in salon music should never be mistaken for triviality. Chopin’s Nocturne in B-flat minor, Op. 9 No. 1, for instance, while a relatively straightforward specimen of Chopin’s contributions to this genre, is a masterclass in subtlety and innovation. The piece destabilises the listener’s sense of metre from its opening bars, and employs dizzying fioratura figures that include groups of eleven notes played against three beats and twenty-two notes against six. Its harmonic language is equally audacious, featuring unexpected modulations and chords that sound startlingly modern. This complexity all serves the work’s expressive goal, creating a dreamlike, introspective atmosphere—an atmosphere perfectly suited to the salon.

Similarly, Liszt’s Consolation No. 3 in D-flat major showcases the genre’s capacity for profound, quiet expression. A clear tribute to Chopin, who had died the year before its composition, the piece adopts the style of a nocturne, with a tender, cantabile melody and a mood of peaceful contemplation. For Liszt, the famous touring virtuoso, a piece of such restraint and intimacy demonstrates the different expressive modes demanded by the salon as opposed to the concert stage. The perceived simplicity of such works is often an illusion; the artistry lies in making formidable technical challenges sound as natural and graceful as breathing, a quality that critics often mistook for a lack of substance.

The Operatic Paraphrase: The 19th Century Remix

Another key salon genre, the operatic paraphrase or fantasia, is often dismissed as a derivative trifle. This view overlooks both its extreme technical demands and its vital cultural function. In an era before recorded music, these pieces were the primary means by which the great melodies of Verdi, Bellini, and Mozart were disseminated to a wider public. Far from being simple transcriptions, works like Liszt’s Rigoletto-Paraphrase were virtuosic reinterpretations, creatively reimagining the opera’s themes through the lens of the piano. They were the 19th century’s equivalent of the modern remix, requiring both compositional ingenuity and dazzling pianistic skill.

The Dance Transfigured

The salon also became the space where functional dance forms were elevated into sophisticated works of art. Chopin took the Polish folk mazurka and the Viennese waltz—dances of the field and the ballroom—and transformed them into complex psychological portraits. His waltzes are often too fast, too melancholy, or too structurally complex for actual dancing, while his mazurkas became vehicles for expressing Polish national identity and a deep, personal nostalgia. They were dances for the mind and the heart, intended for the focused, introspective listening that the salon environment encouraged.

The Hidden Protagonists: Women as Architects of the Salon

No defence of salon music can be complete without acknowledging the central, driving role of women. While the canon of ‘great composers’ has remained until startlingly recently overwhelmingly male—and focused on public genres—the salon was a sphere where women wielded immense influence as curators, performers, and creators. Salonnières were not passive hostesses but powerful cultural brokers who shaped musical tastes, launched careers, and fostered artistic communities. The salon was one of the very few institutions where women could exercise this kind of public-facing intellectual and cultural leadership.

The Salon as a Haven for Women Composers

For women who were largely barred from formal training at conservatories, and from having their large-scale works performed, the salon and its associated genres—the piano miniature, the art song—were the most vital and accessible outlets for their creative ambitions. The career of Cécile Chaminade (1857-1944) is a case in point. Denied entry to the Paris Conservatory by her father, she nonetheless became one of the most popular composers of her era, with her fame spreading as far as New Zealand and the United States—leading to the formation of hundreds of ‘Chaminade Clubs’ dedicated to her music. A leading exponent of the salon style, her elegant and tuneful piano pieces sold millions of copies. Yet her very success—built, I believe, on the quite conscious cultivation of a public image of ‘feminine charm’ that extended to giving her name to a fragrance and having her portrait on cigarette cards—which critics initially praised, also made her vulnerable, when modernist tastes shifted, to a backlash that dismissed her work as superficial.

The Spanish-French mezzo-soprano and composer Pauline Viardot (1821-1910) represents another facet of female power in the salon. A celebrated opera star and formidable intellectual, she presided over one of Paris’s most important musical gatherings, championing the work of Fauré and Saint-Saëns. Her salon was also the primary venue for her own compositions, which drew on a rich tapestry of Spanish, Russian, and French influences and included sophisticated art songs, chamber works, and even operettas. Viardot used her platform not just to promote others, but to establish herself as a major creative force.

The salon, then, represents an alternative, more inclusive musical history. Within its walls, composers like Chaminade, Viardot, Mélanie Bonis, and Teresa Carreño were not ‘minor’ figures but celebrated and influential artists. To dismiss salon music is to perpetuate the erasure of the primary artistic sphere in which 19th-century women could achieve creative and professional success. Its defence, therefore, is a necessary act of historical recovery.

The Enduring Echo – Why Salon Music Matters Today

The decline of the salon’s reputation was not a natural consequence of artistic failure, but rather the result of a complex process of deinstitutionalisation. The loss of legitimacy was driven by new players in the cultural field, such as art dealers, critics, and artists, who strategically created and supported alternatives to the traditional salon system. This provides a crucial causal explanation for the criticism: the music’s reputation suffered not because of a change in its intrinsic quality, but because the institution that supported it was challenged and ultimately dismantled by new market forces and aesthetic paradigms.

The lessons from the rise and fall of salon music are profoundly relevant today. As institutions that have long defined artistic value face their own pressures, the enduring value of the salon model—a space for intimate, intentional gathering and artistic exchange—has led to a modern ‘resurgence of salon culture’. Modern ‘house concerts’ and intimate venues are a rejection of the anonymous, transactional nature of the large concert hall. Just as social media have enabled closer contact between musicians and audiences in the digital space, the intimacy of the salon recreates this proximity in the physical realm. This contemporary revival is not just about performance, but about creating inclusive and accessible events that foster a sense of community. In an age often characterised by digital isolation and the impersonal scale of algorithm-driven mass entertainment, the values championed by the salon—intimacy, community, and a direct, human-scaled connection between artist and audience—feel more necessary than ever.

Salon music was not a trivial, second-rate art form. It was a sophisticated, multi-functional genre that served as a catalyst for social progress, a crucial professional network for serious composers, and an integral part of a curated, holistic aesthetic experience. A true appreciation of salon music requires listening not just with one’s ears, but with an understanding of its history—a history that is inextricably tied to people, place, and a culture that valued intimacy and intentional community over grand, public display.

The salon reminds us that the value of art is not a static property but is constantly defined and redefined by institutional forces, social trends, and aesthetic biases; it invites us to re-engage with music in a personal and interactive way. To truly appreciate art, whether a 19th-century nocturne or a contemporary piece, we must first understand its full context. It is time to listen past the stereotypes of faded wallpaper and tinkling pianos and to rediscover this rich repertoire. At their best, these works are not superficial trifles but beautifully crafted, emotionally resonant artifacts from a world that understood music’s powerful ability to forge deep connections between people from very different backgrounds in a shared, intimate space. To dismiss them is a terrible mistake.