[wp-reading-progress-ert]

My survey of my favourite Grieg Lyric Pieces continues with ‘Little Bird’, from the op. 43 set. Originally titled Fruhlingslieder (Spring Songs) and first published in 1887, this set focuses on the theme of nature, and is a highlight of the entire collection. Choosing just one piece from this album is a real challenge! But this clever little piece is so evocative, you really can imagine Grieg gazing through the window of his hut, watching the rhythms of nature, his imagination captivated by the darting and diving of the birds.

Formal and Pedagogical Economy

From a structural perspective, ‘Little Bird’ is a masterpiece of economy. The piece is built from just a few musical ideas, which are then developed and repeated. The form can be interpreted as either a ternary (ABA) or, with the repeats observed, a strophic (AABABA) structure, with a brief codetta. This repetitive design is a key pedagogical feature of Grieg’s work. The piece is structured in such a way that there’s much less material to learn than there is to play, which means that a small amount of focused practice can lead to quick and noticeable improvement across the entire work. This repetition reinforces the learning process, allowing the pianist to internalise and perfect the technical and expressive elements with each successive iteration.

The table below provides a structural overview of the piece:

.

| Section | Bar Numbers | Key Area | Primary Musical Ideas |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 1–8 | D minor | Fluttering demi-semiquaver motif, descending dotted rhythm, drone bass |

| B | 9–20 | A minor | Inverted fluttering motif in bass, ambiguous chords, Neapolitan harmony, sequential development |

| A’ | 21–28 | D minor | Fluttering motif with new broken chord accompaniment |

| Codetta | 29–36 | D major | Transposed B-section harmony, delicate ascending tonic chords in dotted rhythm |

The piece begins with its central musical material: a ‘fluttering’ demi-semiquaver motif, followed by a descending figure in a dotted rhythm (see ex. 1). The rhythmic character of the entire movement is fundamentally iambic, creating a sense of ‘hopping’ here, rather than a swinging feel. This rhythmic foundation is pervasive and gives the piece its distinctive, sprightly character.

Note how, even in a piece not directly related to traditional Norwegian culture, Grieg’s deep immersion in folk music is evident here through the subtle, yet extensive, use of drone basses and pedal notes. This is not merely a stylistic flourish; it is a fundamental aspect of Grieg’s compositional thought.

Odd Roar Aalborg, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The B-section, bars 9-20, which modulates to the dominant (A minor), introduces an harmonic ambiguity in bars 9–11, a B♭ chord with a diminished fifth. This chord imparts a distinct ‘Neapolitan flavour’. The Neapolitan chord (♭II), typically found in first inversion, is used here in root position, creating a more surprising, ‘heavier’ effect. This sudden introduction of a distantly related, non-functional harmony gives the music its unique, compelling colour. The resolution of this harmonic tension, at bar 12, is as effective as it is simple: the B♭ and D of the chord simply slide down a semitone to A and C♯, a melodic and harmonic device that makes the subsequent arrival of the dominant major chord feel like a significant event.

The B-section then proceeds with a melodic development. Note how the disposition of the material is inverted, the fluttering motif now appearing in the bass at first. Following a sequential descent of the fluttering motif, repeated octave leaps vividly illustrate the little bird hopping from one branch to another, each time higher up, until it reaches the top of the tree, before rapidly descending again.

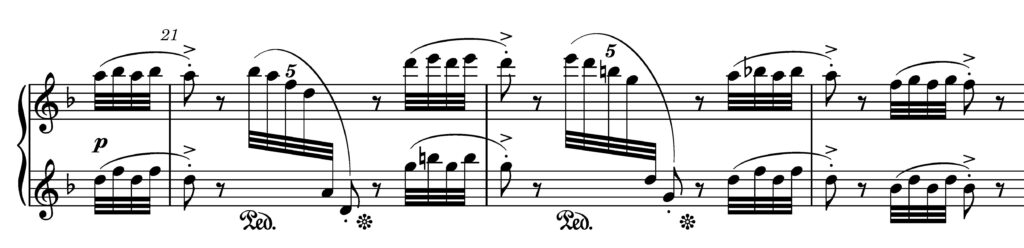

When the A-section returns in bar 21, it is with a significant variation. The simple drone that punctuated the first statement of the fluttering motif is now replaced with a ‘swooping’ descending arpeggio (see ex. 2). This is a prime example of Grieg’s developmental skill: rather than a simple repetition, an enriched restatement expands the musical characterisation of the bird in flight.

The brief codetta, bars 29-36, mirrors the harmonic progression of the B-section, transposing the Neapolitan progression down a perfect fifth. It is with a series of delicate, ascending broken chords in a dotted rhythm as the little bird finally flies out of sight, bringing the piece to a charming conclusion in the tonic major.

Performance Suggestions: Bringing ‘Little Bird’ to Life

This movement’s etude-like nature presents several specific technical challenges that, once mastered, allow us to achieve Grieg’s intended evocative portrayal. The fluttering demi-semiquaver motif, in particular, requires perfect hand synchronization and seamless transitions between the right and left hands. To achieve the requisite lightness and speed, it is crucial to focus not only on depressing the key quickly, but also on releasing it just as quickly.

To capture the piece’s delicate, fleeting character, we must pay close attention to touch and voicing. The B-section and the codetta present the specific challenge of achieving a true pianissimo. In these instances, we shouldn’t shy away from using the una corda (left) pedal to help achieve a delicate tone-colour.

A significant interpretive detail in ‘Little Bird’ is the shifting of the accent in bars 13–20, where Grieg places the accent on the upbeat quaver. This rhythmic nuance is key to avoiding a rigid, metronomic feel and creating a sense of forward momentum and life. This deliberate rhythmic variation lends the music a spontaneous, characterful quality.

The use of the pedal here presents an interesting paradox. The notated pedal markings, such as in bars 1–4, can seem contrary to the notated staccato articulation. A solution to this is to experiment with ‘after-pedalling’—a technique where the pedal is depressed immediately after the note is struck. This allows for a good amount of resonance to be caught, preserving the detached character of the articulation while avoiding a totally ‘dry’ sound.

This approach to pedaling is consistent with broader Romantic-era practices, where pedal markings are not considered ‘set in stone’ and must be adapted to the acoustics of the performance space and the unique qualities of the specific instrument. For further colour and nuance, you can also explore the expressive use of partial pedal changes, such as half or quarter pedals, to create subtle sonic effects and prevent the music from sounding sterile.

The descriptive title is more than a simple label; it is a vital interpretive tool. By giving the piece a clear programmatic subject, Grieg provides us with a roadmap for bringing the music to life. The ‘fluttering’ motif naturally suggests a light, non-legato touch, while the sequential ‘swooping’ passages guide the performer’s dynamic shaping and use of rubato. The narrative of the bird hopping from one branch to another provides a physical and musical metaphor for navigating the sequential passages and helps connect the intellectual analysis of structure and harmony with the physical, expressive act of performance.

Despite its brevity, ‘Little Bird’ is a perfect, concise example of Edvard Grieg’s genius for compressing complex musical and technical ideas into a miniature form. The piece serves as a microcosm of his unique style, showcasing his folk-inspired innovations, his deceptively simple yet profound harmonic language, and his remarkable pedagogical vision. It is a joy for performers of all levels to engage with Grieg’s music, allowing the little bird truly to take flight.