Although I rarely have cause these days to paddle in the balmy waters of the lower grades of the ABRSM syllabus, a little piece on the 2023-24 Grade 4 set works list caught my eye, and so I wanted to share my thoughts on it, for various reasons. First, of course, it’s a nicely-crafted little piece, which is full of potential for atmosphere and feeling for students to enjoy exploring. Second, and not insignificant, is that it is by Franz Liszt, who is one of my favourite composers, but who is also not a chap who’s well-known for making things easy and, as a result, I think this is only the fifth time I have ever encountered his work on a grades syllabus. Sadly, it is an ‘alternative’ piece on the syllabus, meaning it isn’t printed in the exam pieces collection, so without a little more initiative on the part of teacher or student is more likely to be overlooked, so my third reason is promotional.

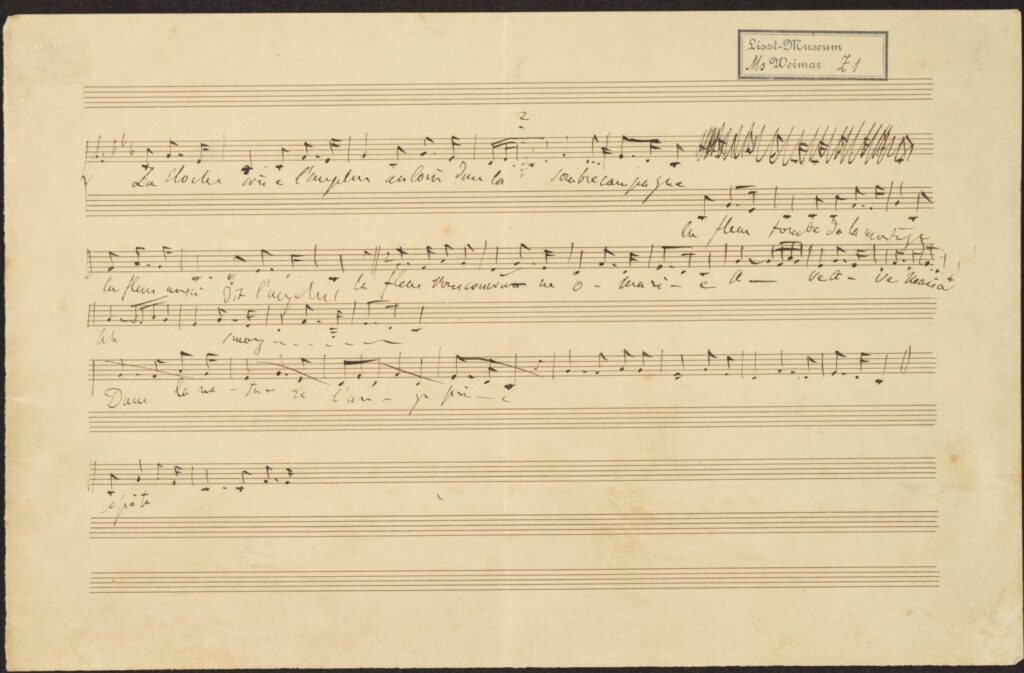

La cloche sonne nicely exemplifies one of my favourite little sayings: a single manuscript can change the world. It was first published as a piano piece in 1958, from a manuscript originally in the Liszt Museum and now in the collection of the Goethe- und Schiller-Archiv in Weimar, Germany (shelfmark GSA 60/Z 1). Thanks to their wonderful digitisation project (an initiative blissfully well-funded and widespread throughout European research libraries) it is now available online, under a public domain licence, which means I can include it here.

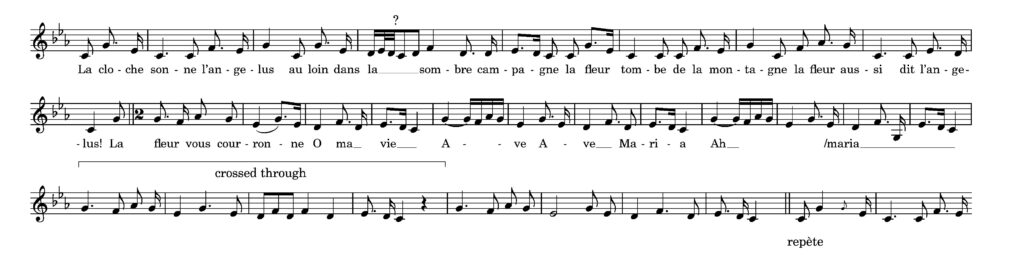

And here are my diplomatic transcriptions:

(Obviously, there are no bar numbers in the manuscripts; I’ve added them for ease of reference.)

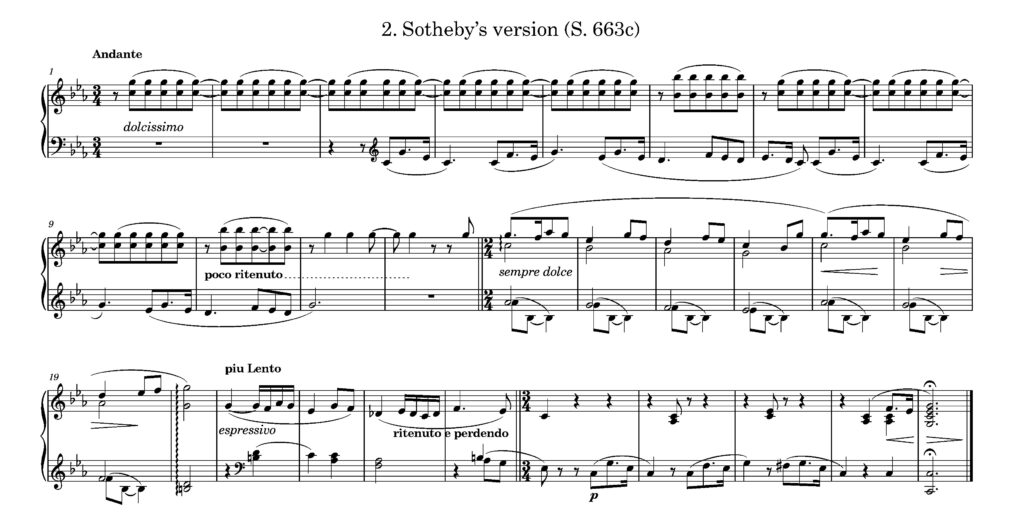

Previously, the work was believed to be based on an unknown French folk song, and is still catalogued as such, for instance, on IMSLP. No-one has ever been able to trace the folk song itself, and this is where the ‘changing the world’ happens, because another manuscript appeared for auction at Sotheby’s in 2019, and was subsequently published by the Liszt Society. There is a fabulously clear image of the manuscript on their website.

https://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2019/rbl-pf1923/lot.86.html

And here is my diplomatic transcription of this version:

The inscription at the bottom reads: ‘L’Angelus – mélodie de Madame la Baronne Amable de Béville, notée par son très humble serviteur’ (‘The Angelus – melody by Madame la Baronne Amable de Béville, notated by her most humble servant’), and signed by the composer. This strongly suggests that it is not based on a folk song at all, but rather on a melody composed, more or less, by the Baroness de Béville.

Baroness Adélaïde-Marie Yvelin de Béville

While I haven’t been able to dig up much about her, the Baroness indeed seems to have been rather a fascinating character. She was the author of a small pamphlet La vie de Marie, a collection of nine canticles intended, so the cover says, ‘to be sung in all the offices celebrated in honour of the most blessed Virgin’ (‘destinés à être chantés dans tous les offices célébrés en l’honneur de la très-sainte vierge’). They were published as an offering of ‘denier de Saint-Pierre’, a donation to the Holy See. You can read them online—thanks this time to the digitisation project at the Bibliothèque nationale de France—and they are very similar indeed to the text of La cloche sonne, leaving little doubt as to the veracity of Liszt’s inscription. The Baroness also wrote another pamphlet, a copy of which has so far eluded me, La charité de l’avenir (Paris and Brussels: Régis Ruffet, 1865), which is listed in the 1865 Journal général de l’imprimerie et de la librairie (Volume 9, Issue 1, page 65, for those of you who care). She pops up again, somewhat incongruously, in the Comptes rendus hebdomadaires des séances de l’académie des sciences, vol 63 (July-December 1866) (Paris: Gauthier-Villars, 1866), with a ‘communication relative au choléra’, specifically ‘the use of lemon as an anti-poison for the most subtle venoms and in particular for cholera’.

Most interestingly, a somewhat weightier tome, Le Livre de toute la vie: Jésus, premier bonheur, dernier espoir (Paris: Malé, 1865) also furnished texts for a musical publication of her own composition, Cantiques du livre de toute la vie (Paris: Malé, 1866) for four-voice choir and organ, which publication was reissued by Ruffet around 1872.

Liszt was kind of awesome

Before getting into more of the musical nitty-gritty, I think this situation itself is worth noting for what it tells us about Liszt. Despite spending the 1860s touring extensively in Germany, Austria, Italy, France, Belgium, and even England and Russia, he was also engaged in 1861 as Director of Music at the Vatican, Pope Pius IX being among his many great admirers. In this role, which he held until 1865, he oversaw music—and, indeed, played the organ—for many services. His own religious faith is well-known, and his extensive output of choral works attests to the inspiration he drew from it. It was perhaps during one of his stays in Rome that he met the Baroness de Béville, although there is no reason that they didn’t meet when Liszt was residing in Paris in the 1830s and 1840s. According to the Sotheby’s listing, the later manuscript is accompanied by a letter from Rome dated 10th September 1866. In it, according to the lot description, Liszt writes of the inadequacy of music to capture certain emotions, and thanks the Baroness for her inspiring Angelus.

Looking again at the ‘melody page’ of the earlier manuscript, I am reminded of those times when one of my younger students had ‘composed’ something and needed my help writing it down. There is here a certain rough-and-readiness that I recognise, with corrections and alterations—in particular, the question-mark above the third bar makes me smile—which comes from taking dictation from someone not necessarily completely clear in intention, trying to fix in writing something that comes out slightly differently with each rendition. That Liszt—who was at this point as celebrated a musician as anyone had ever been, not to mention a pianist and composer of the most exceptional accomplishment—took the time, in a lifetime of frantic productivity, to be of help to the Baroness, and to do so with such good grace, professionalism, and charm, speaks volumes about his generosity and humility. That he turned her melody into such an effective musical miniature is yet further proof, if any were needed, of the incredible fertility of his creative mind.

The second manuscript gives the instrumentation ‘Harmonium (or Pianoforte)’, and the dating of the letter places this piece alongside other original harmonium works and arrangements for the harmonium that Liszt made towards the end of the 1860s. The harmonium version is now officially catalogued as S.663c, while the ‘piano’ version is S.238. It’s worth bearing in mind, of course, that the Weimar manuscript doesn’t actually specify an instrument; it was assumed that it was for the piano. So, while the later manuscript offers us the benefit of some performance directions, of which the Weimar version is completely devoid, the piano seems to me to offer a more appropriate sonority to the tolling effect of the repeated notes in this piece and, as I will discuss later, I think some departure from Liszt’s markings will enhance that image more fully.

But first, let’s look at the Baroness’s words and melody, because it gives us our interpretative bearings. The text, at least as much of it as has been preserved in Liszt’s manuscript, reads:

la cloche sonne l'angelus au loin dans la sombre campagne la fleur tombe de la montagne, la fleur aussi dit l'angelus la fleur vous couronne, O ma vie Ave, ave Maria, ave, ave Maria dans la nature l'ange prie

the bell tolls the Angelus far away in the dark countryside the flower falls from the mountain, the flower, too, says the Angelus the flower crowns you, oh my life Ave, ave Maria, ave, ave Maria In nature the angel prays

(Before anyone pounces, the correct French orthography is angélus, I know; but my expertise is, alas, insufficient to say whether this was the case in the 1860s. In the later manuscript, the inscription does have several accented characters, but ‘angelus’ persists, so I’ll leave it as Liszt wrote it.)

What is the Angelus?

The Angelus is a Catholic prayer of Marian devotion, with origins as far back as the 11th century. A part of the daily liturgy, it is a Versicle and Response, interspersed with three recitations of the Hail Mary (the Ave Maria mentioned in the Baroness’s poem) and followed by a prayer. It is usually recited three times daily, at Matins, Prime and Vespers, and accompanied by the ringing of the Angelus bell, which serves as a calling of the faithful to prayer. The Angelus bell is traditionally rung in three groups of three peals. The text is as follows (the Hail Marys are omitted):

Angelus Domini nuntiavit Mariæ, Et concepit de Spiritu Sancto. Ecce ancilla Domini. Fiat mihi secundum verbum tuum. Et Verbum caro factum est. Et habitavit in nobis. Ora pro nobis, Sancta Dei Genitrix. Ut digni efficiamur promissionibus Christi.

The Angel of the Lord declared unto Mary, And she conceived of the Holy Spirit. Behold the handmaid of the Lord. Let it be done to me according to thy word. And the Word was made flesh. And dwelt among us. Pray for us, Holy Mother of God. That we may be made worthy of the Christ's promises.

The angel in question, of course, is Gabriel; the story, that of the Annunciation. So, the text paints a picture of the tolling Angelus bell, ringing across the dusky landscape, perhaps from the mountaintop, the rural setting, the countryside and the mountain, and the flower’s response to the call to prayer, all mix a Romantic pantheism into the historical imagery of the liturgical rite.

Subtle tone-painting

The detail above is more than mere background because Liszt’s tone-painting is, I believe, quite precise. The introduction can be seen, and phrased, as three groups of three bell-peals, the traditional Angelus pattern, the first two peals of each three echoing back to us, something like this:

(More advanced players might experiment with half- or three-quarter-pedalling to make this even more effective.)

This pattern continues in the accompaniment until bar 11: chime-echo, chime-echo, chime. As the piece progresses, of course, Liszt relaxes this rhythmic scheme, which is exactly as it should be. The coherence of the piece as a whole should always take precedence over a strict adherence to something like musical imagery. The aim is to create an effective musical structure, not merely an accurate impersonation. The bell-effect does persist in the middle section, too, with the repeated dominant pedal note in the lowest voice.

Note also that, despite being in the key of C minor, there are only three B♮s in the entire 29 bars of the piece, and Liszt avoids A𝄬 entirely until bar 13. This gives the first section a modal flavour, which adds to the air of religiosity (and, indeed, also explains the initial assumption that the melody was a folk song).

The music

The piece can be seen either as an altered ’rounded binary’ structure, having two distinct sections and a codetta based on the A-section, or as a ‘truncated ternary’ form, with the A-section repeat halved in length and altered to provide harmonic closure. The A-section, beginning with a three-bar introduction, presents an eight-bar melody in triple time, characterised by a dotted rhythm on the upbeat. (Take care, by the way, not to bump when the phrase begins on the offbeat.) The compass of the A-section melody is contained within the perfect fifth, tonic to dominant; this allows a mutual reinforcement between the melody and accompaniment through shared overtones. Unusually for a piece at this level, the melody is entrusted to the left hand—another selling-point, if it were needed.

The B-section, bars 13-24, in duple time, presents a new melodic idea in the soprano voice, in the relative major. Alto and tenor voices in descending thirds fill in the V7-I progression, which descends over a tolling dominant pedal. The turn back to C minor at bar 20 ushers in a reshaping of the B-section melody, before the triple meter returns to close with an altered version of the A-section melody.

Notice also how the A-section opens and closes ambiguously: the absence of a third in the opening chord leaves the tonality uncertain until the melody enters, while bars 11-12 hover at the unison dominant and, rather than resolving cadentially, recontextualise the note G when the B-section begins in bar 13 as the mediant of the relative major, in which role it first serves as a sort of dominant 13th appoggiatura.

Liszt also carefully avoids any sense of cadential resolution: despite the key of C minor, it isn’t until bar 20 that we hear a leading-note for the first time. Significantly, this is the first ‘proper’ dominant chord, harmonising the exact dominant note that was left unresolved at the close of the first section, nicely framing the middle section.

This dominant chord is prolonged across the start of the new phrase, and while resolving subtly at bar 22, the strength of the perfect-cadence progression is sapped by the dominant seventh chord being in first inversion and the absence of the fifth from the tonic chord that follows it. This harmonic resolution is not the focus of the phrase in bars 21-25 in any case: that honour is bestowed upon the Neapolitan sixth in bar 23, one of only two chromatic alterations in the entire piece. It is a striking moment, proof that less is more—and that even a virtuoso as flamboyant as Liszt had the good musical sense to understand this. Although the Neapolitan is used in its traditional way, that is, as an altered supertonic preparation for a perfect cadence, that cadence itself (bars 24-25) is less than emphatic, landing on a first-inversion tonic chord, and the texture dissipating to only two voices.

One point to note is that there are several recordings

It is only the re-entry of the first-section melody in the bass that establishes the root-position tonic harmony. The final five bars function as both a codetta and a truncated recapitulation of the first-section. Outlining the progression i-ivc-ic-ivc-i, the harmony here feels not only grounded but, indeed, almost static owing to the tonic pedal beneath the final plagal cadence. The F♯ in bar 27 introduces a little Hungarian seasoning, the augmented fourth deriving from traditional gypsy scales (such as those in the B-minor sonata). Again, Liszt’s refined musical judgement is evident in his varying the repeat just enough to avoid monotony.

The codetta closes with the right-hand chord both providing triadic completion of the opening fifth, an octave lower than where it began. Just as the B-section is framed with the octave Gs, first alone then harmonised, the piece itself comes full circle in the same way.

This is a gem of a piece, ingeniously constructed, with vivid musical imagery and a real sense of atmosphere. I do hope you enjoy it!

Transcriptions of the sources and a performance edition are all available in the download library.

I am grateful to Adam Thomas for his help with musical typesetting.