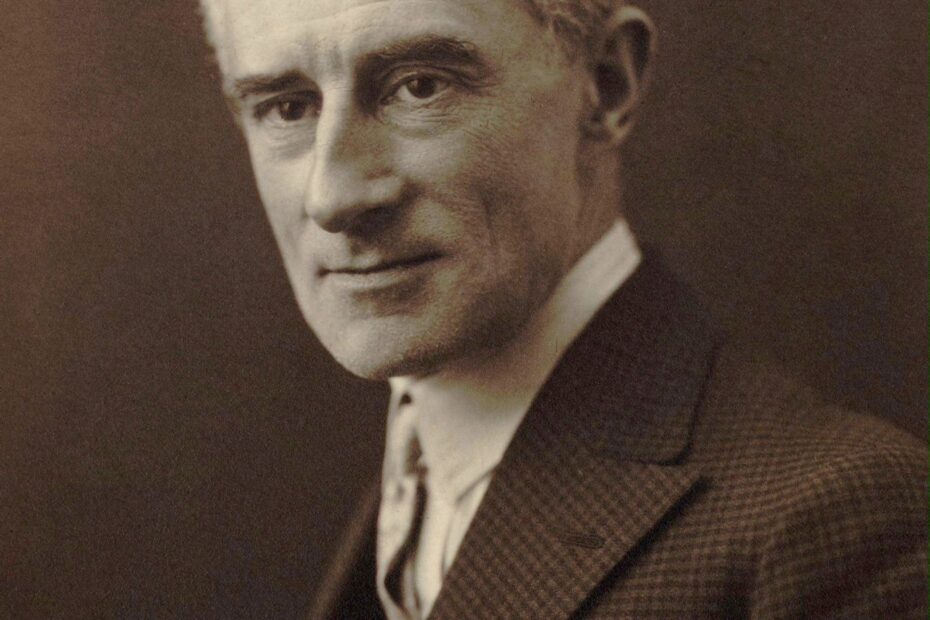

On this day 150 years ago, Maurice Ravel, one of my absolute favourite composers, was born in Ciboure, a Basque town some ten miles from the Spanish border. To celebrate this anniversary, over each of the next six months, I’ll be posting about a work or group of works for solo piano. There’s also an additional members-only post, available now, exploring the labels often mis-applied to this unique composer.

The Paradox of the Basque ‘Swiss Clockmaker‘

Joseph-Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) occupies a unique space in the pantheon of great composers, particularly for his contributions to the piano. Often associated with the atmospheric haze of Impressionism, a label he, like his contemporary Claude Debussy, rejected, Ravel was a composer of profound paradoxes. The most famous of these is encapsulated in Igor Stravinsky’s oft-quoted description of him as a ‘Swiss clockmaker’. This moniker points to the almost fanatical precision, the flawless craftsmanship, and the intricate mechanics that underpin every bar of his music—qualities perhaps inherited from his father, a Swiss engineer who fostered his son’s early talents. His mother, however, to whom Ravel was closer (Édouard, his younger brother, was closer to his father, eventually following in his footsteps and becoming an engineer) was of Basque origin, and had lived in Madrid. This heritage was a constant source of fascination and inspiration to the composer.

Stravinsky’s image of the detached artisan stands in stark contrast to Ravel’s own artistic credo. ‘Great music,’ he insisted, ‘must come from the heart. Any music created by technique and brains alone is not worth the paper it is written on’. He described his own work as ‘intuitive, emotional music’. This series will explore the solo piano works of Ravel through the lens of this central paradox, arguing that the two sides are not contradictory but inextricably linked. Ravel’s meticulous construction—his classicist’s devotion to form, his obsession with textural clarity, and his perfectionist’s ear for sonority—is not an end in itself. Rather, it is the very mechanism through which he builds his unparalleled worlds of dream, emotion, and atmosphere. Like a master watchmaker assembling gears to measure the abstract passage of time, Ravel assembles notes with perfect precision to give tangible form to the intangible realms of memory, water, and night. His classicism is the vessel for his modern sensibility; the mechanism is the key to the dream.

A Chronology

To embark on a journey through Ravel’s solo piano music is to witness the evolution of one of the most original and influential voices of the 20th century. From his earliest student works to his final, poignant masterpiece, his output for the instrument is remarkably visionary in its scope, and consistent in its quality. This table provides a chronological catalogue of the works I’ll be exploring, and as they are released links to each post will be added.

| M. Number | Title | Composition Date | Key / Movements | Dedicatee | Significance |

| M. 5 | Sérénade grotesque | c. 1893 | F-sharp minor | Ricardo Viñes | Ravel’s earliest surviving piano work; a raw and prescient prototype of his Spanish style. Published posthumously. |

| M. 7 | Menuet antique | 1895 | F-sharp minor | Ricardo Viñes | The first flowering of Ravel’s neoclassicism, blending Baroque form with modern harmony. A tribute to Emmanuel Chabrier. |

| M. 19 | Pavane pour une infante défunte | 1899 | G major | Princesse de Polignac | Ravel’s first widely popular work, an archaising piece of profound elegance and modal beauty. |

| M. 30 | Jeux d’eau | 1901 | E major | Gabriel Fauré | A revolutionary work that established a new pianistic language for depicting water, arguably initiating musical Impressionism for the piano. |

| M. 40 | Sonatine | 1903–1905 | F-sharp minor / D-flat major / F-sharp minor | Ida and Cipa Godebski | A masterpiece of neoclassical concision and cyclical form, combining Mozartean clarity with modern sensibility. |

| M. 43 | Miroirs | 1904–1905 | I. Noctuelles (D-flat major) II. Oiseaux tristes (E-flat minor) III. Une barque sur l’océan (F-sharp minor) IV. Alborada del gracioso V. La vallée des cloches | I. Léon-Paul Fargue II. Ricardo Viñes III. Paul Sordes IV. Michel-Dimitri Calvocoressi V. Maurice Delage | A five-movement suite dedicated to members of the “Apaches” circle, marking a shift from representation to subjective reflection. |

| M. 55 | Gaspard de la nuit | 1908 | I. Ondine (C-sharp major) II. Le Gibet (E-flat minor) III. Scarbo (G-sharp minor) | I. Harold Bauer II. Jean Marnold III. Rudolph Ganz | Inspired by Aloysius Bertrand’s gothic poems, it is the pinnacle of transcendental virtuosity in the piano repertoire. |

| M. 58 | Menuet sur le nom d’Haydn | 1909 | G major | Joseph Haydn | A tribute for the centenary of Haydn’s death, ingeniously based on a musical cryptogram of his name. |

| M. 61 | Valses nobles et sentimentales | 1911 | Suite of 7 waltzes and an epilogue | Louis Aubert | A modern deconstruction of the Viennese waltz, inspired by Schubert, featuring advanced harmonies that shocked its first audience. |

| M. 65 | Prélude | 1913 | A minor | Jeanne Leleu | A brief but brilliant and virtuosic competition piece. |

| M. 63 | À la manière de… | 1913 | 1. Borodine (D-flat major) 2. Chabrier (C major) | 1. Alfredo Casella 2. Jeanne Leleu | Two witty and masterful stylistic pastiches, demonstrating Ravel’s deep understanding of other composers’ idioms. |

| M. 68 | Le Tombeau de Couperin | 1914–1917 | I. Prélude II. Fugue III. Forlane IV. Rigaudon V. Menuet VI. Toccata | Each movement dedicated to a friend who died in World War I | Ravel’s final major solo piano work; a neoclassical suite that serves as a poignant and deeply personal war memorial. |

Returning momentarily to Stravinsky’s ‘watchmaker’ comment, this is not necessarily pejorative. Remember, Ravel and Stravinsky were close friends who admired each other’s work. They were both members of the Parisian avant-garde artistic group known as ‘Les Apaches’ (‘The Hooligans’), a circle of artists who considered themselves outcasts, and championed new music. Their interactions were part of a lively dialogue among the era’s most innovative composers. Their mutual respect was evident in their opinions of each other’s compositions:

Ravel was an early and staunch supporter of Stravinsky’s work. He held a particular fondness for Stravinsky’s ‘Russian period’ ballets (The Firebird and Petrushka). He was one of the few who immediately grasped the monumental importance of The Rite of Spring, recognising it as a groundbreaking masterpiece and predicting its premiere would be an event of historical significance comparable to Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande. However, Ravel was less enthusiastic about Stravinsky’s later, postwar neoclassical and atonal works, such as Les Noces.

Stravinsky, in turn, held Ravel’s work in high regard. He famously called Ravel’s ballet Daphnis et Chloé ‘one of the most beautiful products of all French music’. His famous description of Ravel—’the most perfect of Swiss watchmakers’—was a nod to Ravel’s Swiss heritage and, more importantly, a compliment to the meticulous precision, intricate detail, and flawless craftsmanship that defined his compositions—qualities Stravinsky himself valued.

As colleagues in Paris, they collaborated on at least one project, working together on an orchestration of Modest Mussorgsky’s opera Khovanshchina in 1913. Their musical styles also show signs of mutual influence. Both composers were master orchestrators who shared an interest in jazz harmonies and folk traditions. Ravel was present as Stravinsky was composing The Rite of Spring, and its revolutionary harmonies are thought to have influenced Ravel’s later work, particularly the powerful and chaotic climax of La Valse.

Despite their strong initial bond, the friendship between the two composers eventually cooled. The primary catalyst for this shift was an incident surrounding Ravel’s ‘choreographic poem’, La Valse. In 1920, Ravel performed a two-piano version of the piece for the impresario Sergei Diaghilev, hoping he would stage it as a ballet. (The other pianist was Marcelle Meyer, a student of Cortot, Long, and Ravel’s long-time friend and collaborator Riccardo Viñes; she was the favourite pianist of Les Six.) Stravinsky was present at this private audition. Diaghilev rejected the work, regretting that, although it was a masterpiece, it was ‘not a ballet… it’s the portrait of a ballet’. Ravel was deeply hurt by the rejection, but, having expected his support, was further wounded by Stravinsky’s silence during the confrontation. After this event, they reportedly spoke very little. Even with this personal falling out, though, a deep-seated professional respect remained. Stravinsky attended and spoke at Ravel’s funeral in 1937, a final acknowledgment of the profound connection they shared as two of the 20th century’s most important musical minds.