It is commonly supposed among us pianists that the ring finger

To be sure, the thumb is larger and heavier, but in terms of pianistics—a magnificent term I first encountered in Cortot’s edition of Chopin’s Études, and which I have since endeavoured to use at least once daily—the thumb really needs to be considered as a different species of digit entirely. But still the idea of weak fingers, most particularly the fourth but also the fifth, persists. Let me tell you, in pianistic terms, there is no such thing as a weak finger, there is only poor finger-use.

Let’s first apply a bit of commonsense before going on to examine why this idea of weak fingers came about, and why it has persisted for so long.

The commonsense: a thing you might have heard of called YouTube offers countless examples of brilliant young pianists playing all sorts of challenging stuff. It would follow that, if sheer physical strength were a pre-requisite for pianism, no child would have the ‘muscularity’ to rattle off a Rach 2 or Tchaik 1, but they do. Even when they’re out of the prodigy phase, not all great pianists resemble 18-stone bodybuilders. Yes, weight might help, especially when you’re trying to make enough sound to fill a large hall, but there has to be more to it than just strength.

So, whence comes this concern with strength, and the corollary dread of ‘weak fingers’?

We need to go back to the early days of the piano, the late eighteenth century, to find our answer. During its infancy, the piano resembled the harpsichord far more closely than it did the modern piano. It was only with the Industrial Revolution and the addition of the cast-iron frame that the body of the instrument could bear the tension generated by the strings that the expansion of the piano’s range demanded; all-wood frames buckled and warped. If the early instrument physically resembled the harpsichord, the digital control of dynamics and attack would surely have made people think of the clavichord, an instrument so small and incapable of projection it was considered suitable for teaching and practice, but not really for performance. The idea of ‘piano technique’ as distinct from ‘harpsichord technique’ had not really evolved, and so the earliest published keyboard tutors—the market for which flourished as the instruments proliferated throughout the homes of the wealthy and not-so wealthy middle-classes in the emerging urban centres of Western Europe—did very little to address the increasingly different technical demands of the piano to those of its predecessors, whose shallower key-beds and lighter actions required no involvement of the body beyond the hand. Of course, an Érard from the 1830s would feel heavy to anyone used to a Walter from the turn of the 19th century. The instinctive response to needing to move a heavier weight is to get stronger. The idea of ‘lifting the fingers high’ and developing ‘independence’ really originates here. The mechanism of the harpsichord is such that the ‘fingers-only’ approach is effective. But as soon as the key has to move further, and there is more action-weight behind the key, the fingers alone are insufficient to the task.

What follows may be taken to summarise what I consider to be ‘neutral’ or ‘default’ technical advice; in certain circumstances due either to physical individuality or musical necessity, practice may of course differ. But for me, the best practice is that which works with the body and the instrument. It is this approach that enables the best playing, because the pianist is as free as possible from strain and tension. It is also the healthiest approach, as it minimises the risk of injury, and permits the pianist to enjoy many hours of work without fatigue.In terms of working with the body, I will restrict the following discussion mainly to the use of the finger and hand, as this post is about the myth of weak fingers (and, you will probably have gathered, the pointlessness of working to strengthen the fingers in isolation).

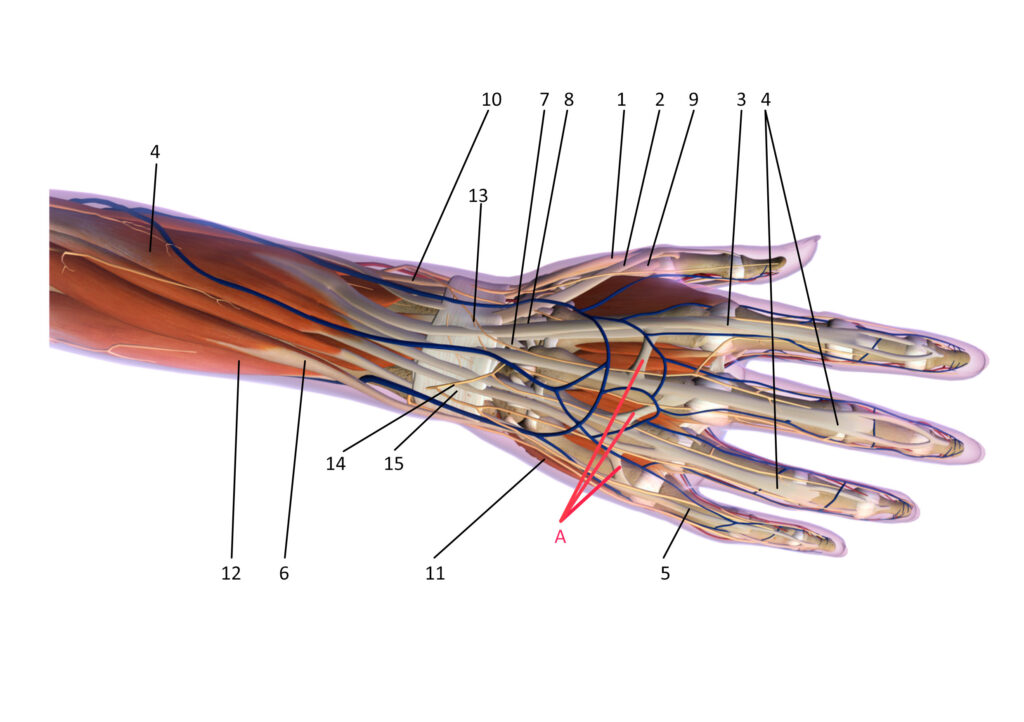

A whistlestop tour of the anatomy of the top of the hand.

The straightening of the fingers is performed by tendons called extensors: the extensor pollicis brevis, and extensor pollicis longus (1 and 2) work the thumb. They are involved in straightening the thumb, for instance, to reach larger intervals. The extensor pollicis brevis (1) works the metacarpophalangeal and carpometacarpal joints (the two sections of the thumb from the wrist), while the extensor pollicis longus (2) controls the distal phalanx (the nail joint). Lifting the thumb in the same direction as the fingers, however, involves the abductor pollicis longus (10), which lifts the thumb so mimics the pianistic function of the finger extensors. The thumb is lowered by the adductor pollicis (9), which lies mainly beneath the hand (the palmar or volar side), where it divides into the transverse head, which connects to the mid-palm beneath the middle finger, and the oblique head, which connects the the opponens digiti minimi, that lovely big chunk of meat on the palm of the hand behind the little finger. This is responsible for carrying the thumb beneath the hand for legato scale-playing, etc., those movements we collectively refer to as ‘passing the thumb’.

So far, so irrelevant, in so much as, while the thumb is a complex part of the apparatus capable of larger and smaller movements in a very wide range of motion, this doesn’t impact on the so-called weakness of fingers, particularly the fourth. The extensors in question are the extensor digitorum (4), which branch off from the extensor digitorum communis muscle, which lies on the upper surface of the forearm. The index and little fingers also have unique extensors, the extensor indices (3), and the extensor digiti minimi (5), which respectively enable the individual straightening of the index finger, as when pointing, and of the little finger, as when drinking tea from a fine china cup. The little finger is also controlled by the abductor digiti minimi (11), which separates the fourth and fifth fingers, so again helps with wider intervals and larger chords.

Just to complete the discussion of the illustration above, also marked are: the extensor carpi radialis brevis and extensor carpi radialis longus (7 and 8 respectively), which raise the hand, that is, draw the top of the hand towards the forearm; and the extensor carpi ulnaris (6), which serves the same function as 7 and 8, but on the opposite side of the forearm, promoting balance and control of strength, and it also enables adduction of the wrist, that is drawing the ‘little-finger side’ of the hand towards the side of the forearm, resulting in a straighter alignment of the forearm and thumb. The flexor carpi ulnaris (12), wraps around the upper forearm, but is primarily involved on the underside of the forearm, helping perform the exact opposite function of 6.

The entire apparatus is given sensation by the radial and ulnar nerves (13 and 14 respectively).

So, here is why the fourth finger is accused of weakness.

As indicated A above, as well as being organised by the extensor retinaculum (15), a dense membrane sheath that holds everything in place as it travels through the wrist, the finger extensors are also joined laterally by ‘intertendinous connections’. The first and second finger are connected and the fourth is connected to both the third and fifth fingers. The third finger is, in fact, also slightly impinged by its connection to the second. To demonstrate this, make a fist (thumb out of the fingers’ way), and straighten the index and middle fingers only. Now try to return the index finger to the fist, leaving only the middle finger extended. (For cultural reasons, this experiment is best performed alone!) The middle finger needs to compromise its degree of extension before the index finger can return fully.

The reason that the fourth finger is considered weak, while the middle finger isn’t, however, comes from the position of the intertendinous connections. Those between the third and fourth, and fourth and fifth connect to the third and fifth fingers closer to the palm joint, which restricts the independent extension of the fourth finger much more severely than that between the second and third, which is more perpendicular and further behind the metacarpo-phalangeal joint (the knuckles where the fingers attach to the hand.)

Some people also argue that impingement is increased by both of the fourth finger’s intertendinous connections being crossed on both sides by nerve branches, but I am not convinced that this has as significant an effect as the intertendinous connections themselves. After all, the human body is a miraculous jumble of nerves, veins, capillaries, arteries, and so on. While the term ‘muscle-bound’ refers to someone who has developed certain muscles to an exaggerated and unnatural extent, to the point where muscular bulk inhibits the body’s full range of motion—imagine, for example, being unable to place your hands on your shoulders because your biceps got in the way—it would seem to be a gross error of design that the human body can be, say, ‘vein-bound’ or ‘nerve-bound’ by default. That said, the fourth finger, uniquely, is innervated by both the radial and ulnar nerves, so perhaps this makes for a more complicated neurological situation when it comes to controlling this digit in isolation, and this additional challenge to our co-ordination increases our perception of the fourth finger’s ‘weakness’.

Either way, playing the piano is no more an activity for which the human body has evolved maximum efficiency than is body-building. The human hand is naturally best at grasping, because grasping is vital for many survival skills. The thumb is opposable for a reason; but there is no evolutionary need for it to have an equal range of motion in the opposite plane.

And here is why it doesn’t matter.

All of the above has discussed, primarily, the extensors, those tendons responsible for straightening and lifting the fingers and hand. Playing the piano, however, involves depressing keys. Pianists don’t straighten our fingers, we round them. We use flexors, not extensors, and flexors have no intertendinous connections. Strictly speaking, there is no need for us to lift our fingers beyond the height of the key; and if we permit relaxation and the weight of the action to lift the key after we have pressed it, there is no need for us to lift our fingers at all.

Yes, for the anatomical reasons discussed above, if we are trying to lift each of our fingers ‘high’ above the surface of the key and use each with total independence from the others, we are going to feel weakness, particularly in the fourth finger. Independence is a foolish idea, as if each finger were not connected to the same hand, wrist, arm, and brain; never mind that some fingers are literally connected to each other. Yet even as great a pianist as Liszt began his technical exercises with various combinations of resting and active fingers in various combinations.

Now, I don’t want to throw the baby out with the bath-water; and I don’t believe Liszt didn’t know what he was doing. There is a purpose to finger isolation exercises, but it is not the development of physical strength, rather of strengthening neural pathways. Making sure that only the correct bit of the mechanism gets the message. To quote the neuropsychologist Donald Hebb, “neurons that fire together wire together”. Practice is as much about the mental as it is about physical.

As I described above, the tendons that control individual fingers all connect to one muscle, the hands and fingers are innervated by ever smaller and finer divisions of two main nerves, the ulnar and radial. Larger mechanisms of movement divide into smaller units, but everything is connected. Although I have described above the main functions of each part of the apparatus under consideration, almost none of them work in total isolation. Especially in complex movements, like playing the piano, smaller parts will work in tandem with larger parts; our aim is only to involve each to the extent that is necessary. To say we play the piano with our fingers is like saying we run with our toes. Just as the upper body contributes as much to running as do the legs and feet, pianism requires the co-ordinated involvement of the entire body. All the finger-strength in the world won’t help you if you’re trying to play Rach 3 sitting sideways to the piano and cross-legged!

I said at the outset that there is no such thing as a weak finger, only poor finger-use. This is not the place to go into what constitutes good finger-use, especially as I would say that means good use of the hand, wrist, forearm, elbow, upper arm, shoulder, and back. I’ve gone on long enough already for now! Let’s save something as straightforward as what makes the perfect piano technique for next time… Suffice it to say, though, that if your finger, wrist, and forearm are aligned—most importantly, that the arm-weight is behind the active finger—no finger will feel weak. A practical fingering helps enormously; good finger-use depends on good fingering.

A word on alignment.

Before signing off, a brief word on alignment. I said that if your finger, wrist, and arm are aligned, that if the arm-weight is behind the active finger no finger will feel weak. What I mean by this is you should aim to make a straight line from the elbow to the active finger. Take a five-finger exercise, and try it two ways. First, holding the wrist still, trying not to clench, and using only the fingers from the palm joint. Second, allowing the wrist to swing laterally to find a straight alignment through the arm to the active finger. At slower speeds, you might feel little difference, according to your level of proficiency; but as you accelerate, I guarantee that the second way will feel stronger and more in control. This will actually reduce the amount of work required of the fingers, as the weight of the arm will be engaged to move the key, the fingertip becomes the point of contact through which that weight is transferred into the piano action. When the mechanism is not aligned, the finger not only has to do more work to depress the key, but is also working against the misplaced arm-weight—just as we change our gait when we carry a heavy backpack, in order not to fall backwards.

Finger isolation exercises do have their place, as I said, but their purpose is to strengthen co-ordination, not to strengthen the finger. They are best done with good alignment, as in fact are any technical exercises. Let’s forget all of that old-school ‘penny on the back of the hand’ nonsense! If you stop fighting the fingers’ interdependence, find the most ergonomic means of deploying your playing apparatus