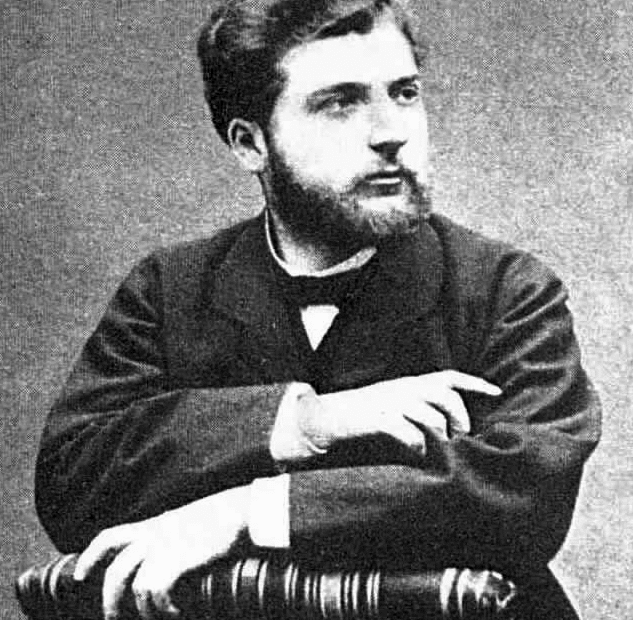

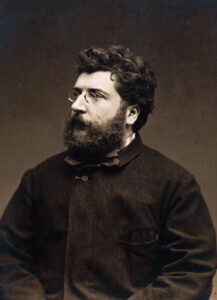

On this day exactly 150 years ago, the French composer Georges Bizet died from a heart attack. He was 36 years old. He never saw the enormous success of his opera Carmen, and went to his grave believing himself a failure. This post explores the composer’s small output for the piano; and I will go on to examine each work in greater detail in a series of members-only posts, in celebration of this tragic and underrated composer.

The Pianist in the Opera’s Shadow: Bizet’s Paradoxical Relationship with the Keyboard

The legacy of Georges Bizet (1838-1875) is dominated by a single, towering masterpiece: the opera Carmen. This work, along with the orchestral suites from L’Arlésienne and, to a lesser extent, Les pêcheurs de perles, has so completely defined his public identity that other facets of his musical genius have been all but eclipsed. Chief among these neglected areas is his work for solo piano, a body of music whose obscurity is directly linked to a central paradox in the composer’s life: Bizet was a pianist of prodigious, internationally recognised virtuosity who actively suppressed this aspect of his ability.

A Virtuoso in Denial

Bizet was not merely technically competent; rather, his gifts were extraordinary. A brilliant student at the Paris Conservatoire, which he entered at the prodigiously young age of nine, he accumulated the institution’s highest honours, winning Premiers Prix for piano, organ, fugue, and composition. His keyboard prowess was not just academic. In a famous encounter in 1861, Bizet met Franz Liszt, the 19th century’s definitive piano titan. After Liszt performed one of his own fearsomely difficult works, Bizet, undaunted, sat at the piano and sight-read the piece flawlessly. The astonished Liszt declared, ‘I had thought that there were only two men capable of struggling victoriously against the difficulties with which I enjoyed peppering this piece; I was mistaken; there are three of us, and the youngest of us is perhaps the boldest and most brilliant’. Yet, unlike his contemporaries, he chose not to capitalise on this skill. He was, by all accounts, ‘ambivalent about the piano’ and rarely performed in public, writing to a friend, ‘I find the performer’s trade an odious one’.

Operatic Ambition

Bizet’s denial of his pianistic gifts was driven by a singular, all-consuming ambition: to be recognised as a composer for the lyric stage. In the musical world of Second-Empire Paris, opera was the undisputed path to fame and success. Bizet worried that the public would primarily view him as a pianist rather than a composer, a fear that led him actively to sabotage a potential career as a concert virtuoso.

This ambition proved difficult to realise. The main Parisian opera houses were reluctant to gamble on new works, preferring the established repertoire. As a result, Bizet’s career as a composer stalled, and his orchestral and keyboard compositions were, by and large, ignored.

The Drudgery of the Day Job

The profound irony of Bizet’s career is that his refusal to be a concert pianist forced him directly into the domestic piano market to earn a living. His exceptional keyboard and sight-reading skills made him the ideal candidate for what historians have bluntly termed ‘hack composition work’. He became a prolific arranger and transcriber for music publishers like Choudens and Heugel. This work entailed creating piano-vocal scores, solo piano arrangements, and four-hand duets of other composers’ operas, choral works, and orchestral pieces. The sheer volume of this labour is staggering. Musicologist Hugh MacDonald notes that over 6,000 pages of these arrangements were published under Bizet’s name during his lifetime, compared to a scant 1,500 pages of his original works. This ‘day job’ consumed the time and creative energy that could have been dedicated to his own piano compositions.

However, this commercial drudgery had a critical, if unintentional, artistic consequence. By spending thousands of hours preparing scores for Gounod, Reyer, and Thomas, Bizet was given an insider’s view of the operatic market. He was forced to solve the problems of reducing orchestral and vocal scores to something that could be manageably played by amateurs at home. This daily grind directly shaped his compositional style. The orchestral and ‘operatic’ textures that define his mature solo works are not an accident; they are the direct result of his transcription career.

Defining the Corpus: What is Bizet’s ‘Solo Piano Music’?

Any critical discussion of Bizet’s piano music must first confront a significant challenge: catalogue confusion. For the public, Bizet’s ‘brand’ is Carmen, and thus the most-performed ‘Bizet piano music’ consists of transcriptions of his operas usually arranged by other pianists—from popular ‘Habanera’ arrangements to virtuosic concert works like Vladimir Horowitz’s Carmen Variations.

This confusion is compounded by Bizet’s own catalogue. His most successful original keyboard work is Jeux d’enfants, Op. 22 (1871). This is widely hailed as masterful, but it is scored for piano four-hands, not solo, which places it outside the scope of this survey. Therefore, the true original solo piano oeuvre is a small, twice-neglected body of work: overshadowed first by his monumental operas, and second by his own more popular duet and transcription works. These original solo pieces were composed primarily in two distinct periods: those of his student years (1851-1857) are strongly Chopinesque; while those of his mature period (1865-1868) are more eclectic and ambitious.

Here is a categorised list:

| Category 1: Original Solo Piano | Category 2: Original Piano Duet (Four-Hands) | Category 3: Transcriptions of his own orchestral/stage works |

| Variations chromatiques de concert, Op. 3 (1868) | Jeux d’enfants, Op. 22 (1871) | L’Arlésienne Suite No. 1 (1872) |

| Chants du Rhin (1865) | L’Arlésienne Suite No. 2 (arr. 1872) | |

| Chasse fantastique (1865) | ||

| Nocturne in F major (c. 1854) | ||

| Nocturne No. 1 in D major (1868) | ||

| Grande valse de concert (1854) | ||

| 3 Esquisses musicales (c. 1858) | ||

| 4 Preludes (c. 1854) |

Bizet’s earliest works for solo piano were composed while he was studying at the Conservatoire. Stylistically, they are heavily influenced by Chopin, reflecting the prevailing taste of the Parisian salon. This group includes the Nocturne in F major (c. 1854), the Grande valse de concert, and the Trois esquisses musicales.

These pieces demonstrate that the young Bizet was not just a technical prodigy but a precocious composer with a fully formed lyrical and harmonic gift. The Esquisses, for example, range from the warm lyricism of the Sérénade to the playful pianistic flair of the ‘Caprice’. The Nocturne in F major, written when Bizet was 16, serves as an excellent case study. It is a confident assimilation of the Chopinesque idiom, featuring a lilting melody over a gentle chordal accompaniment. Its balance of poetry and technical accessibility makes it a perfect example of the salon miniatures that characterise this period. These early works show a complete mastery of the pianistic salon idiom before his operatic transcription work pushed his style in a more orchestral direction.

After returning from his Prix de Rome residency in Italy, Bizet re-engaged with the piano between 1865 and 1868. These later works are more eclectic, showing a composer moving beyond imitation and synthesising his influences—particularly Liszt and Mendelssohn—with his own theatrical and programmatic instincts.

The Chasse fantastique (Fantastic Hunt) of 1865 signals a clear shift in Bizet’s style toward the more grandiose. It is a concert étude in the manner of Liszt, a virtuosic tone-poem for the piano. While some critics have found it somewhat melodramatic, it is more accurately understood as hyper-characteristic of Bizet’s core ambition. It represents his first major attempt to merge Liszt’s programmatic virtuosity with his own dramatic obsession. It serves as a vital bridge from his Chopinesque salon pieces to his orchestral concert works.

Bizet’s most significant programmatic cycle for piano is Chants du Rhin. Composed in 1865, this collection of six miniatures bears the subtitle ‘Songs for piano’, in a clear homage to Mendelssohn.

The cycle is not abstract; it is a direct musical translation of a series of poems by Joseph Méry. The poems, which were published in Le Ménestrel in 1866 , preface each of the six pieces: L’Aurore (Dawn), Le Départ (The Departure), Les Rêves (Dreams), La Bohémienne (The Gypsy Girl), Les Confidences (Confidences), and Le Retour (The Return). This explicit literary programme reveals Bizet’s clear preference for music with a narrative underpinning, and his instinctive feel for tone-painting.

The Variations chromatiques de concert, Op. 3, is Bizet’s most ambitious work for piano, his final major statement for the instrument, and his only set of variations. This was a work of serious, personal importance to the composer. He wrote to a friend in July 1868, ‘I have just finished some Grandes variations chromatiques for piano… I’m completely happy with this piece, I can tell you. The treatment is very daring, as you will see’. It is precisely this ‘daring’ quality that has drawn modern scholarly attention.

While this survey focuses on original solo works, a critical examination of Bizet’s own solo piano transcriptions of his L’Arlésienne Suites (1872) is essential. Alphonse Daudet adapted the play in 1872 from his original story, which was included in his 1869 collection Letters from My Windmill. It flopped, but the music gained instant popularity. Bizet, therefore, skillfully scored his own orchestral music for the piano, primarily to serve the domestic market. Unlike other composers’ arrangements, these are a legitimate and final part of his compositional output. Pianist Julia Severus, for instance, closes each of the two discs in her complete cycle for Naxos with one of these suites, cementing them as a coda to his original oeuvre.

Georges Bizet’s solo piano music does not—and was never intended to—revolutionise the repertoire in the manner of Chopin or Liszt. Its obscurity is the direct result of the composer’s own operatic ambitions, the ‘hack work’ that consumed his time, the ‘shadow repertoire’ of transcriptions that eclipsed his original works, and his tragically early death. Its primary value is twofold. First, it stands as a collection of admirable works of high craft. Second, and more importantly, the music’s value lies in its function as a private laboratory. It is the connective tissue between Bizet the brilliant pianist and Bizet the supreme opera-dramatist. In works like Chants du Rhin, he sketched the programmatic landscape and ‘gypsy’ themes that would define his theatrical future. In his ‘hack work’ and in the daring, orchestral Variations chromatiques, he forged the very techniques of musical drama, thereby preparing the essential ingredients of his own musical and theatrical masterpieces. For Bizet, sadly for us, the piano was never the main stage; it was the rehearsal room.